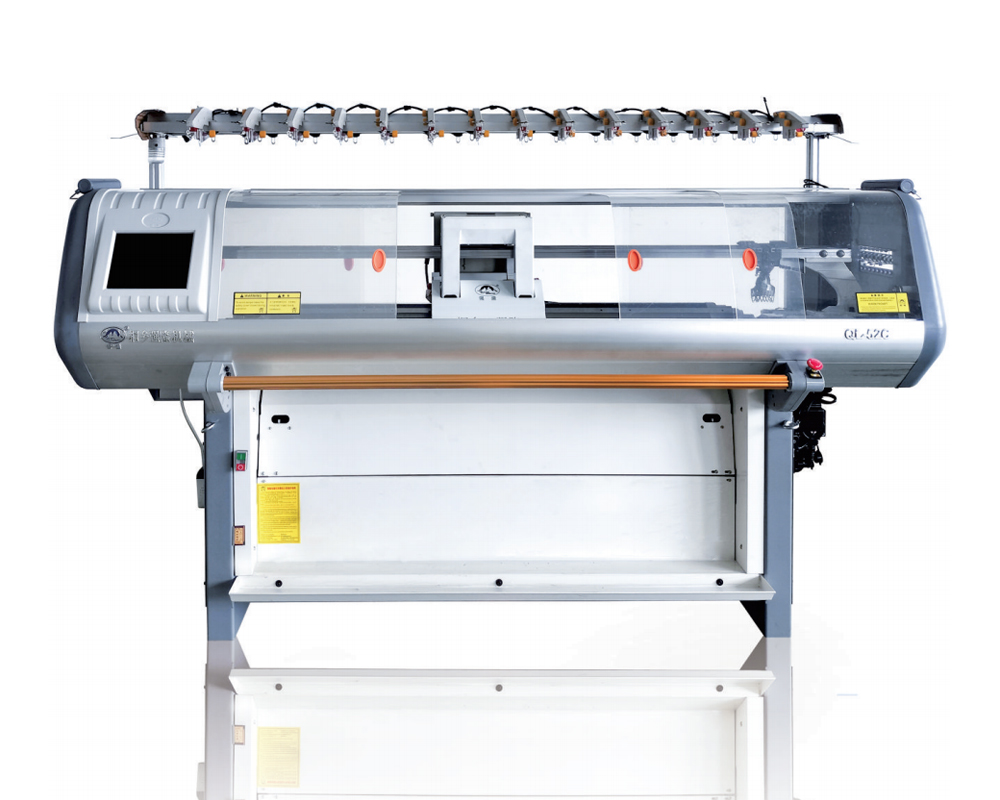

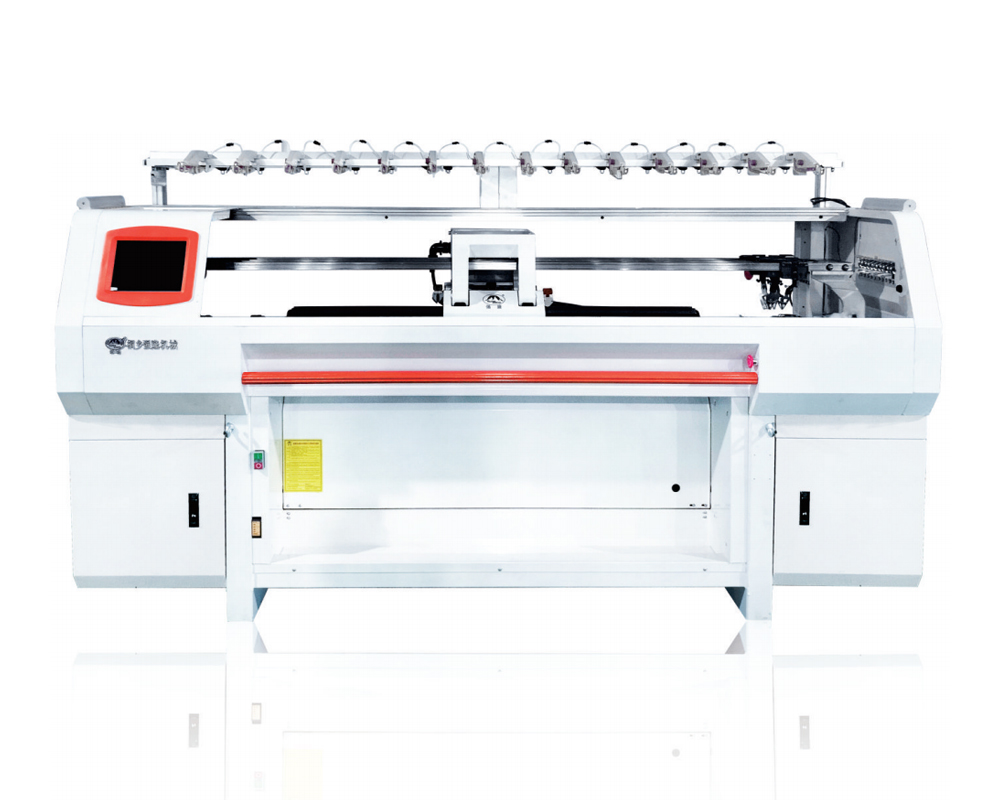

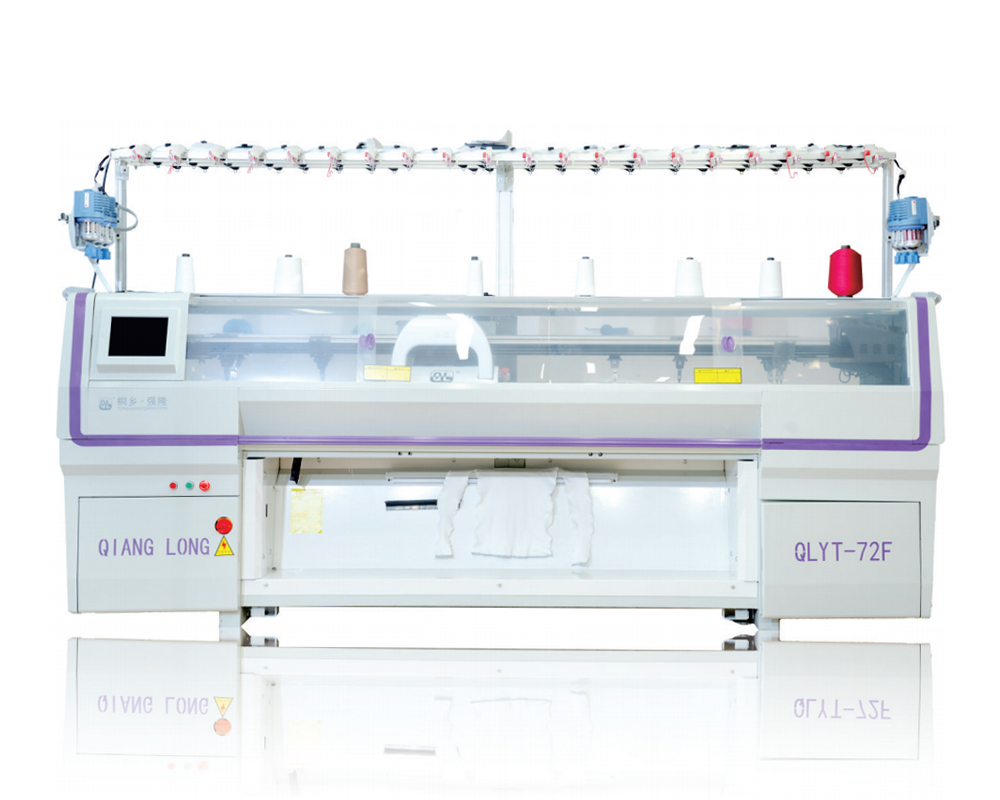

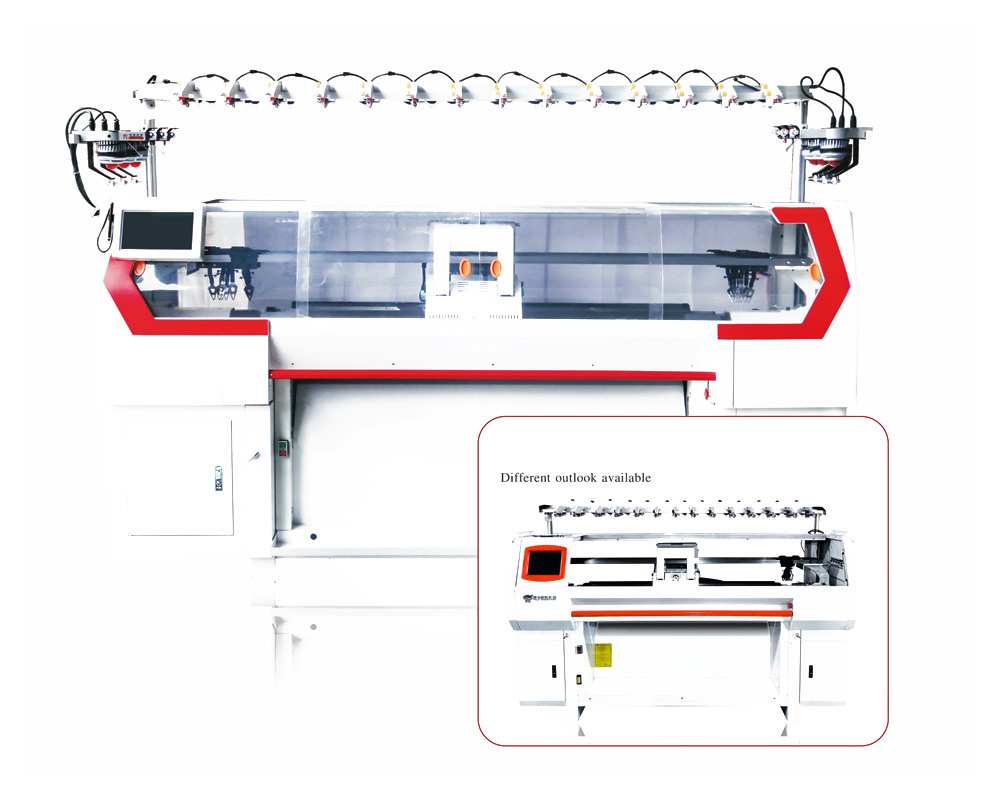

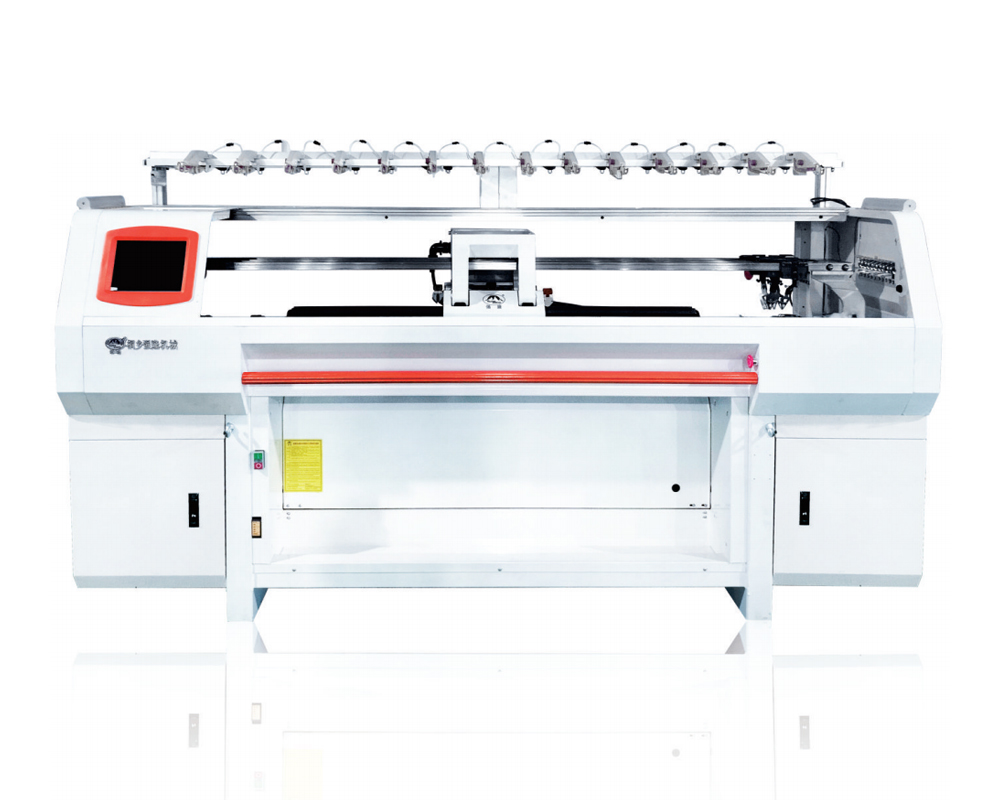

Tongxiang Qianglong Machinery Co., Ltd. is high-tech China wholesale computerized flat knitting machine manufacturers, specialized in designing, developing, and manufacturing Knitting Machinery..

Understanding the Fundamentals of Knitting Machine Programming

Programming modern computerized flat knitting machines requires a foundational understanding of how digital instructions translate into physical knitting operations. Unlike traditional manual machines where operators directly control needle selection and carriage movements, computerized systems interpret coded instructions that specify every aspect of the knitting process including needle selection patterns, carriage direction, yarn feeder activation, and stitch formation techniques. The programming language varies by manufacturer, but all systems share common elements that define the relationship between digital commands and mechanical actions. Learning to program begins with understanding this translation process and recognizing how basic knitting operations are represented in the machine's software interface.

The core concept underlying all knitting machine programming involves breaking down complex fabric structures into sequences of individual knitting courses, where each course represents one complete traverse of the carriage across the needle bed. Within each course, the program must specify which needles are active, what type of stitch each needle should form, which yarn feeders are engaged, and any special operations such as transfers, tucks, or needle movements. Modern zero waste yarn systems integrate directly with this programming framework, optimizing yarn consumption by calculating exact yarn requirements for each programmed design and minimizing waste through precise tension control and efficient pattern layouts. Mastering programming means developing the ability to visualize how sequential course-by-course instructions build complete three-dimensional knitted structures.

Setting Up Your Programming Environment and Software

Before beginning actual programming, operators must properly configure the software environment and establish communication between the computer and knitting machine. Most modern flat knitting machines utilize dedicated CAD/CAM software packages provided by the machine manufacturer, though some universal programming platforms support multiple machine brands. The initial setup involves installing the software on a computer system meeting the manufacturer's specifications, typically requiring Windows operating systems with adequate processing power and memory to handle complex pattern calculations and simulations. USB or network connections link the computer to the machine controller, enabling program transfer and real-time machine monitoring during production.

Software configuration requires inputting specific machine parameters including gauge specification, number of needles on front and back beds, available yarn carriers, and mechanical capabilities such as transfer systems or pattern attachment compatibility. These parameters define the programming environment's constraints, preventing the creation of programs that exceed the physical machine's capabilities. User preferences can be configured for measurement units, display options, default yarn counts, and simulation viewing angles. Understanding the software interface layout is essential, with most systems featuring multiple windows or panels displaying pattern design areas, stitch programming grids, yarn management tools, and machine status information. Familiarizing yourself with toolbar locations, menu structures, and keyboard shortcuts significantly improves programming efficiency as skills develop.

Basic Stitch Structures and Their Programming Codes

All knitted fabrics are constructed from combinations of fundamental stitch structures, each represented by specific codes or symbols in the programming interface. The knit stitch, the most basic structure, involves a needle holding a loop and knitting a new loop through it, represented in most systems by a filled square or the letter K. The tuck stitch holds the old loop while adding a new loop to the same needle without clearing the previous loop, creating textural effects and increasing fabric width, typically coded as T or shown with a specific symbol. The miss or float stitch skips knitting on a selected needle while the yarn floats behind, used for creating patterns and colorwork, generally coded as M or left as an empty space in pattern grids.

| Stitch Type | Common Code | Function | Visual Effect |

| Knit | K | Forms standard loop | Smooth, basic fabric |

| Tuck | T | Holds old loop, adds new | Textured, wider fabric |

| Miss/Float | M | Skips needle, yarn floats | Pattern creation, stranding |

| Transfer | X or arrow | Moves stitch to another needle | Shaping, lace effects |

| Cast On | CO | Creates initial loops | Starting edge formation |

| Cast Off | CF | Secures final loops | Finishing edge |

Understanding how to combine these basic stitches creates infinite pattern possibilities. Programming interfaces typically display stitch patterns in grid format where rows represent knitting courses and columns represent individual needles. Entering stitch codes into grid cells defines the stitch type for each needle in each course. Simple patterns might repeat the same stitch across all needles, while complex designs vary stitch types according to specific patterns. Learning to read and create these grid patterns forms the foundation of all programming work, as even the most sophisticated three-dimensional structures ultimately consist of carefully sequenced combinations of these fundamental stitch types arranged across multiple courses and needles.

Creating Your First Simple Program from Scratch

Beginning programmers should start with the simplest possible fabric structure—a plain stockinette rectangle—to understand the complete programming workflow from design to finished fabric. Open a new project in the programming software and define the basic parameters including fabric width in needles, desired length in courses, and yarn selection from the machine's available carriers. For a first project, program a 100-needle width using 200 courses of plain knit stitches on the front bed. The software interface provides tools to fill selected areas with specific stitch types, so select the entire grid area and fill it with knit stitches. Add cast-on instructions at the beginning and cast-off instructions at the end to create finished edges.

Before transferring the program to the machine, utilize the software's simulation feature to visualize the knitting process and verify the program logic. Simulation shows the carriage movements, needle selections, and progressive fabric formation course by course, helping identify programming errors before wasting time and materials on the actual machine. Check that the cast-on engages the correct needles, that yarn carriers activate at appropriate times, and that the cast-off properly secures the final course. Save the completed program with a descriptive filename indicating the fabric type, dimensions, and yarn used. Transfer the program to the machine controller via USB or network connection, load the specified yarn onto the designated carrier, and execute the program while monitoring the knitting process to compare actual results with the simulated visualization.

Implementing Shaping Techniques Through Fashion Programming

Fashion programming, also called fully-fashioned knitting, creates shaped garment panels by progressively increasing or decreasing the number of active needles during knitting, producing pieces that conform to body contours without requiring cutting. Programming increases involves bringing additional needles into action on either edge of the knitting, expanding the fabric width gradually. The software provides increase commands that specify which needles to activate and at what intervals, with common approaches including activating one needle every course for rapid shaping or one needle every several courses for gentler curves. Decreases work oppositely, deactivating edge needles progressively to narrow the fabric, programmed similarly by specifying which needles to drop and the decrease frequency.

- Sleeve shaping typically programs decreases from shoulder to wrist, starting with perhaps 120 needles at the sleeve cap and decreasing to 60 needles at the cuff over the programmed sleeve length

- Neckline shaping requires more complex programming with simultaneous decreases on both sides plus specialized center front decreases creating the neck opening curve

- Armhole shaping combines rapid initial decreases to create the underarm curve followed by gentler decreases shaping the shoulder slope

- Zero waste programming optimizes shaping sequences to minimize yarn consumption by calculating exact yarn requirements for each course and adjusting tension accordingly

Advanced shaping techniques employ partial knitting, where only a portion of the active needles knit in specific courses while others hold their loops. This technique creates three-dimensional shaping such as shoulder slopes, bust darts, or heel turns in socks. Programming partial knitting requires specifying the needle range that knits in each course, with the carriage reversing direction before reaching the fabric edge. The held needles accumulate rows while the knitted section progresses, creating the dimensional depth necessary for ergonomic garment shaping. Mastering partial knitting programming enables creation of complex three-dimensional forms directly on the machine without subsequent sewing or assembly.

Pattern Design and Multi-Color Programming

Creating patterned fabrics with multiple colors or textures requires coordinating needle selections with yarn carrier assignments across multiple courses. Intarsia programming creates distinct color blocks where different yarns knit on different needle groups within the same course, requiring the software to manage multiple carriers simultaneously and prevent yarns from tangling. Each color area is defined as a separate region in the pattern grid, with the program automatically generating the necessary carrier movements and needle selections. Fair Isle or jacquard programming creates all-over color patterns by alternating yarns while using miss stitches to carry non-knitting yarns across the back of the fabric, with pattern repeats defined in the software and automatically replicated across the fabric width.

Most programming software includes pattern libraries with pre-designed motifs, textures, and color arrangements that can be imported and incorporated into custom programs. These libraries accelerate development by providing tested pattern elements that can be combined, scaled, or modified rather than programming every stitch manually. Custom patterns can be created using drawing tools within the software or by importing bitmap images that the software converts into stitch patterns based on user-defined rules for translating pixel colors to yarn selections and stitch types. Pattern programming for zero waste systems includes optimization algorithms that analyze the design and suggest modifications to reduce float lengths, minimize yarn breaks, or improve material efficiency while maintaining the intended aesthetic effect.

Transfer Techniques and Lace Structure Programming

Transfer operations move stitches from one needle to another, enabling creation of lace patterns, rib structures, and complex textural effects impossible with basic knit-tuck-miss combinations. Programming transfers requires specifying the source needle holding the stitch, the destination needle receiving it, and the timing within the knitting sequence. Simple transfers move stitches between adjacent needles on the same bed, while more complex operations transfer stitches between front and back beds, creating tubular fabrics or intricate structural patterns. The software interface typically represents transfers with arrows indicating movement direction, and programs must ensure destination needles are empty before receiving transferred stitches to prevent needle collisions that damage the machine.

Lace programming combines transfers with yarn-over operations where needles knit without holding previous loops, creating the characteristic open holes and decorative patterns of lace fabrics. A typical lace pattern sequence involves transferring a stitch from one needle to an adjacent needle, leaving the source needle empty, then knitting the next course where the empty needle creates a yarn-over while the needle holding two stitches knits them together, forming a decrease that balances the increase. Programming these sequences requires careful attention to stitch counts, ensuring increases and decreases balance to maintain consistent fabric width. Modern software includes lace pattern generators that create these complex transfer sequences automatically from simplified design inputs, significantly reducing programming complexity for decorative open-work fabrics.

Optimizing Programs for Material Efficiency and Zero Waste

Zero waste yarn computerized knitting systems integrate advanced programming features that minimize material consumption and eliminate waste throughout the production process. Yarn consumption calculation tools analyze the complete program and compute exact yarn requirements for each carrier, accounting for stitch types, fabric dimensions, and tension settings. This precision allows operators to prepare yarn packages containing exactly the required amount plus a small safety margin, avoiding the excess yarn typically wound onto cones that remains unused after program completion. The software can suggest program modifications that reduce yarn consumption, such as adjusting stitch densities in non-critical areas or optimizing increase/decrease sequences to minimize edge waste.

Nesting and layout optimization features help programmers arrange multiple garment pieces or products within the machine's needle bed capacity to maximize production efficiency and minimize yarn waste between pieces. The software can automatically calculate optimal spacing between pieces, share common edges where possible, and sequence production to minimize yarn carrier changes and machine downtime. Tension optimization algorithms adjust yarn feeding rates based on stitch types and fabric structures, ensuring consistent fabric quality while using the minimum yarn necessary for each stitch formation. These efficiency features transform programming from simply defining the desired fabric structure to comprehensively optimizing the entire production process for sustainability and cost-effectiveness, aligning with modern manufacturing priorities for resource conservation and environmental responsibility.

Troubleshooting Common Programming Errors

Even experienced programmers encounter errors that prevent programs from running correctly or producing the intended fabric. Needle selection errors occur when programs attempt to activate needles outside the machine's available range or create impossible needle combinations such as having both front and back bed needles in transfer positions simultaneously. The software typically flags these errors during simulation, but understanding the underlying causes helps prevent them during initial programming. Careful attention to needle counting and bed assignments, especially in programs involving transfers or complex shaping, prevents most selection errors. Maintaining visual references showing current needle positions helps track which needles hold stitches and which are available for new operations.

Yarn carrier conflicts arise when programs attempt to use multiple carriers in ways that cause physical interference or tangling, such as crossing carrier paths or activating carriers in sequences that create yarn wraps around machine components. Understanding the physical geometry of yarn carrier movement and the machine's carrier rail configuration helps identify potential conflicts during programming. Most software includes carrier path visualization tools that display yarn routes during simulation, revealing conflicts before they occur on the actual machine. Tension-related problems manifest as uneven fabric density, loops dropping from needles, or yarn breaks during knitting, often caused by incorrect tension settings in the program or inappropriate yarn specifications that don't match the actual materials being used. Systematic testing and adjustment of tension parameters while documenting successful settings for different yarn types builds a knowledge base that improves programming accuracy and reduces trial-and-error debugging time.

Advanced Programming Concepts and Continuous Learning

As programmers master basic techniques, advanced concepts open new creative and technical possibilities. Parametric programming creates flexible templates where key dimensions and properties are defined as variables that can be adjusted to generate different sizes or variations without reprogramming the entire structure. This approach is particularly valuable for garment production where the same basic design needs to be produced in multiple sizes—the parametric program automatically scales increases, decreases, and proportions while maintaining the intended design characteristics. Macro programming defines reusable subroutines for commonly used pattern elements or construction techniques that can be called from multiple programs, improving consistency and reducing development time for complex projects involving repeated structural elements.

Continuous learning is essential as machine capabilities and software features evolve rapidly, introducing new techniques and possibilities. Manufacturers regularly release software updates adding features, improving simulation accuracy, or optimizing calculation algorithms. Participating in user communities, attending training workshops, and studying sample programs from experienced programmers accelerates skill development beyond what individual experimentation alone can achieve. Documenting your own programs with detailed comments explaining the logic behind specific techniques creates a personal knowledge base that helps recall solutions when facing similar challenges in future projects. The journey from basic programming competency to advanced expertise is ongoing, with each project presenting opportunities to refine techniques, discover more efficient approaches, and push the boundaries of what computerized flat knitting machines can achieve in creating innovative, zero-waste textile products.

English

English 简体中文

简体中文

Chinese

Chinese English

English